What is a Paragraph?

What Is a Paragraph?

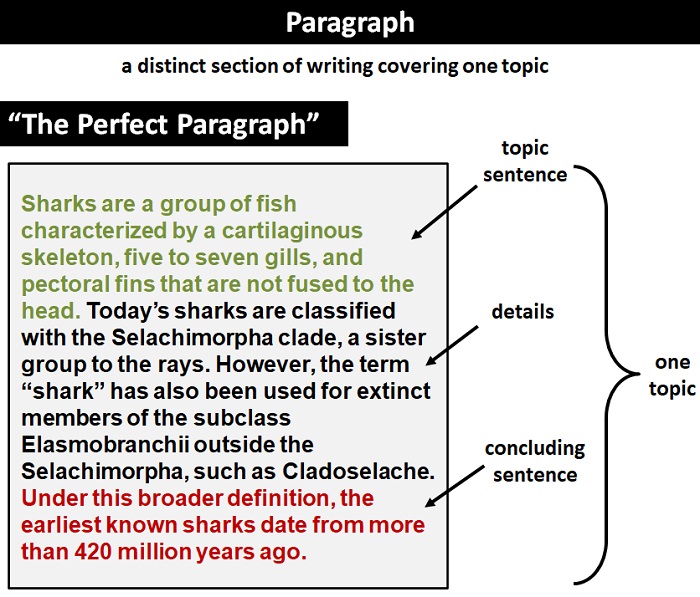

A paragraph is a distinct section of writing covering one topic. A paragraph will usually contain more than one sentence.

A paragraph starts on a new line. Sometimes, paragraphs are indented or numbered. (Whatever format you use, be consistent.)

The "perfect paragraph" will start with a topic sentence. It will have detail sentences in the middle and end with a concluding sentence. It will only cover one topic from start to finish. The length of a paragraph is supposed to be determined by the topic, but often writers will create a paragraph simply to ensure they're not presenting too much text in one chunk.

All this diversity means that it's not always easy to determine what "one topic" means when dividing your text into paragraphs. For example, you could have a one-topic paragraph describing Venus (with the next paragraph describing Mars) or a one-topic paragraph describing the colours of a sunset (with the next paragraph describing its reflection in the sea).

If you're getting the sense that the word topic is a bit too grand for a measly paragraph, then think of a paragraph as a distinct section of writing that covers one aspect of your topic. That's the point. Sometimes, a paragraph will be an aspect of a topic, sometimes it will be a topic within an issue, sometimes it will an issue within an argument…a narrative, a process, a comparison, whatever. Whatever the scope of your paragraph, it should be neatly bounded as one…well, topic. If you prefer aspect instead of topic, go with that.

A Video Summary

Here is a video summarizing this lesson on paragraphs.Why Should I Care about Paragraphs?

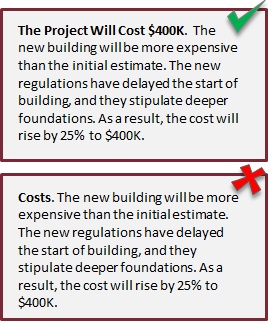

There are three noteworthy points related to paragraphs. One is a good tip, one is a style convention, and one is an observation.(Point 1 - a good tip) In business writing, use paragraph titles.

A good tip for business writing is to give each of your paragraphs a title that summarizes the paragraph content. This serves two purposes. Firstly, it ensures your paragraph topic is neatly bounded, and, secondly, the title will assist busy executives with skim-reading.

(Point 2 - a style convention) Use several "opening" quotation marks if your quotation covers more than one paragraph.

When a quotation contains multiple paragraphs (or is a text with lots of new lines), a common convention is to use an opening quotation mark at the start of each paragraph (to remind your readers that they're still reading a quotation) but only one closing quotation mark at the end of the last paragraph. Look at this example:In 1912, the publisher Arthur C. Fifield sent Gertrude Stein the following rejection letter shortly after receiving her manuscript for The Making of Americans:

"Dear Madam,

"I am only one, only one, only one. Only one being, one at the same time. Not two, not three, only one. Only one life to live, only sixty minutes in one hour. Only one pair of eyes. Only one brain. Only one being. Being only one, having only one pair of eyes, having only one time, having only one life, I cannot read your M.S. three or four times. Not even one time. Only one look, only one look is enough. Hardly one copy would sell here. Hardly one. Hardly one.

"Many thanks. I am returning the M.S. by registered post. Only one M.S. by one post.

"Sincerely yours,

"A. C. Fifield"

"Dear Madam,

"I am only one, only one, only one. Only one being, one at the same time. Not two, not three, only one. Only one life to live, only sixty minutes in one hour. Only one pair of eyes. Only one brain. Only one being. Being only one, having only one pair of eyes, having only one time, having only one life, I cannot read your M.S. three or four times. Not even one time. Only one look, only one look is enough. Hardly one copy would sell here. Hardly one. Hardly one.

"Many thanks. I am returning the M.S. by registered post. Only one M.S. by one post.

"Sincerely yours,

"A. C. Fifield"

(Point 3 - an observation) Your online readers won't read lengthy texts, so use your discretion to keep your paragraphs short.

In print, an unbroken lengthy text looks dull and daunting. On a screen, an unbroken lengthy text looks doubly so. Therefore, dividing a long text into bite-sized topics is essential for keeping your readers engaged. If we're being strict, each of your paragraphs should neatly encapsulate one topic, but, as we've touched upon, the definition of "topic" is pretty slack, and this often gives you some wriggle room to play with your paragraph lengths.Yes, there is a one-topic-one-paragraph ruling, but there's also a need to protect your readers from lengthy texts. Strike a balance or lose your readers.

This sounds like advice to play with the rules for writing a paragraph. Good. It is. If you're unconvinced that readers – particularly online readers – need lots of "whitespace", try Googling "the value of whitespace".

Work through these worksheets to develop you knoweldge and ability to work with paragraphs.

Key Points

- Keep your paragraphs neatly bounded under one topic by using paragraph titles (even if those titles exist only in your head and not on paper).

- Give each paragraph in a multi-paragraph quotation an opening quotation mark. Close the quotation with a closing quotation mark at the end of the final paragraph.

- If you're writing web content, keep your paragraphs short (even if that means bending the one-topic-one-paragraph rule).

Comments

Post a Comment